Published in / Soft Boiled newsletter

…

On a January night, the bus stops in the middle of an eerily empty street. The road’s covered by a fine layer of snow, like sugar. When I get off I feel like lingering around for a while. I walk towards a bench, slump down my bags and think about rolling a cigarette. I don’t smoke much – I bought that packet of tobacco sometimes in early autumn – and still got more than half left. But this moment somehow asks for a cigarette. I realize this might be the first time that I smoke in public in my hometown, and, although I stand in the veil of darkness on a deserted street, it feels, funnily enough, like a personal upheaval. My fingers began to freeze while performing the micro-movements of rolling, and the first cig turns out completely flimsy. The second one looks fine, just in time before my hands fall off, stiffened by the cold. I light it.

The main street is very quiet at this late hour. Eight pm here feels like midnight somewhere else. Once in a few minutes, there’s a person passing by and everyone acts the same: they stare at me and then quickly look away.

It’s always a bit strange, unheimlich, to arrive in my hometown when my mother’s not present. It feels almost like visiting the past that is uncannily realistic. Opening the door of our small apartment and turning on the lights; as if I was entering the life we once had here, me and my mother, in our little fort from which we guarded ourselves against the outside danger – the world, and where we had fought our own dramatic battles, too.

I open the door and what I first hear is the thick silence of things, so very different from my mother’s intense, loud presence.

I unload my body from all the bags and all the layers; my heavy coat, winter boots, and two woolen pullovers, and then I need to take care of the place itself, to let the life in, the juices that make apartments livable, as my mother always puts the place into a state of complete hibernation before leaving for her – other – home. (Just in case something… As usual: just in case.)

I open the water valve. And the gas. Plug in the kettle and the little lamps.

I fling the windows open onto the quiet street and let the draft circuit the stale air that has lingered in the rooms for some weeks already.

For a while, I stand there and gaze out of the bedroom window. Orion’s right there above me in the winter sky, the stars gleaming in the cold.

I know I need to call my mother, I promised, but I keep postponing. First I need to make some tea, then unpack my bags, wash my face, change my clothes for leggings and a hoodie. Then I eat something little in our miniature kitchen. Curl up on the sofa and check tomorrow’s weather, then re-open the app to check the weather in my friends’ cities: Prague, Berlin, Lisbon, Noosa, New York, Shelburne Falls.

…

When I finally make the call, it’s already past 9 pm. So, tell me, how is he? I ask her. My mother’s voice sounds tired, as if it was crumpled, when she tries to summarize the health of her partner, who’s in a hospital at the moment. His state has gotten worse, she reports, she went to see him today, and she’s glad she made the visit. I told him – and this is when she starts crying – I told him that I’m sorry, I’m sorry for everything I had told him when we fought, and he – she weeps – he told me he was sorry too. He was listening to me and then…

I still love him, you know?

My mother’s 73 now, her partner 86. They’ve been together for 7 years. It came unexpectedly, out of the bluest blue when I thought my mother had been the most solitary being on Earth. She locked herself out of those life’s joys and struggles that love brings many years ago, right after I was born. Later she told me that when she couldn’t give me the presence of my father, she did not want me to be exposed to other men who would, probably, all turn into assholes and treat me badly. She made a decision and stuck to it.

I remember thinking it was probably a good decision, an act of self-sacrifice, but later on, as I became a woman myself, once I knew what it means to live in a woman’s body and mind, my perspective changed. There was a moment when I began to realize that this act of utter self-sacrifice was lined with so much self-rejection, cruelness, and I remember being perplexed how is it even possible to make oneself so thin, to set up this rule for oneself, to cast oneself in this restricted form, to cut oneself away from life’s vitality? Or a major part of it.

The complexity of a mother’s choice: She’d say she wanted to spare me the negative experience of a man who would treat me badly, but what if she spared herself and me some good stuff, too?

Maybe it would mean something for me, to see her mirrored in another person’s eyes, to see her happy or angry with someone, not just with myself. And how the gift of complete attention that she gave me had turned ambiguous. Sometimes almost a burden, perplexing: nourishing and suffocating at the same time. And the way she had infused her tremendous gift of self-sacrifice with the bitter taste of guilt that I had taken on as my own, like a skin that was so hard to shed off years later.

I’m still listening to my mother who now talks about edema, the water rising in her partner’s body – she says they tried to take the water out at the hospital as it had already reached the lungs, yet they only succeeded a little, his knees are still swollen looking like some boulders. (How strange, to have one’s body flooded from the inside. To drown in yourself. To be flooded by the water your body is not capable of releasing, I said to my friend some days back).

I know this is the end, my mother weeps: I know it already, I’ve seen it so many times.

I know, mom, I say.

You know nothing, my mother replies in a voice that cuts right through me.

At this moment, while still trying to listen, I nevertheless begin drifting away and find myself scrolling some online shop for linen bedsheets. It’s idiotic, but it’s also some instinct. I guess this is how I seek to distribute the heaviness, by scrolling down the multiple images of perfectly styled bedsheets, thinking “white – light pink – or gray?” What a strange attempt of the mind, as if trying to hyperventilate, fearing to be sucked into my mother’s dark whirlpool where I had been so often, to take on some absurd sense of guilt once again, to drown in her. Yet I feel that it’s not the same, I am not the same, I do feel different now. That after two years of therapy I actually begin to feel some solid ground under my feet. Something has changed; I am able to observe the vortex my mother turns into without being sucked into it, erased by it.

I am aware of this: slowly, painstakingly did I move towards this quiet place where I can stand almost firmly, on my own ground, safe from my mother’s weather.

What would she be, were she a landscape? My mother as geography – I imagine her as a solitary island with all of it: lush green forests and vast patches of arid ground, with sunny days and melancholic rains and scary hurricanes. She can be everything. Sometimes I just long for a soft and windless valley.

Don’t we all want mothers who are like valleys?

Mother – abyss

Mother – wound, I wrote on a scrap of paper the other day and taped it on the wall in my studio. What a beautiful word “wound” actually is, the sound of it that opens up into the unknown. I’ve been thinking whether, with the closest people I have around me, our wounds might be complementary to each other, even magnetic. The scar clan; people who almost instantly feel close because they can sniff out each other’s wounds from the very first moment, long before they actually confide in each other.

I close the tab with the bedsheets, still undecided about the color. Then I hear her say: I’m glad that I told him that, you know, that I apologized for what I had said when we had fights.

It’s good that you had this moment together, mom.

I wish though I had never told him some things, she says.

Don’t think like this – I say – you have both entered this relationship after living two lives that could not be more different, he was in his stale marriage for almost half a century, and you had no one, you were free and independent, a woman with her own mind, so it was natural there was this clash in life perspectives, but you gave each other a lot, you mirrored each other, and you learned a lot about yourself, too, and you’ve been through something you had no idea you’d encounter at this age, after so many years vacant of those feelings…and all of a sudden you were texting me in the middle of the night, my mother who was 67 at the time, saying you don’t know what to do and maybe you are in love.

Haha, that was so crazy! my mother says, and I smile, on the other side, in another town.

And then she adds something I find, in a strange way, touching:

He taught me some good technical stuff, too.

…

We talk for nearly an hour. It’s shortly before 10 pm when I hang up, wishing my mother good sleep and promising I’d come over the next weekend to her – other – home, and bring her the winter boots she lent me. Wouldn’t you come over for two days? she says, and although she doesn’t say how much she needs me at this moment, she’s always too “proud” to ask for help, there’s an underlying urgency in her voice, and I know she might need me like never before. At that moment I feel like I want to caress her in my arms, like a little, weak child.

But you know what – maybe you’ll come right for the funeral, she adds with her signature humor that still protrudes to the surface, despite her exhaustion, despite anything.

My mother’s sarcasm: something to rely on when life gets erratic.

After the call, I stare at the black TV screen for a while. Then some sort of intuitive urgency pulls me out of the sofa. I climb on the armchair and open the closet, feeling almost seduced by that certain shelf with two neat stacks of clothes. It’s not so mystical though; this is the spot where my mother used to keep some of her private stuff, and where I used to peek as a child, hoping to discover a big secret of some kind.

There is something tucked in the very back of that shelf. My hand reaches an orange-red chocolate box meticulously wrapped with a white ribbon that almost looks like some bondage. The object emanates a single word: treasured. How come I never stumbled across this one?

I sit down on the sofa, holding it in my hands, feeling its weight. Slowly, carefully I process to untie the multiple knots. The anticipation builds up, and with each newly conquered knot the intensity of its secret content arises too, vibrates, fills up the living room.

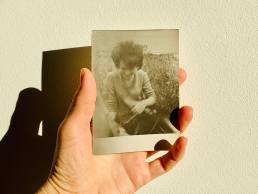

I open the lid and find a stack of letters. Most of them are in envelopes, but the top one is loose. Dear Olga, it says – it turns out this carefully hidden stack of papers are love letters that my mother had received from some guy, decades back.

The letters are from 1974, meaning she was 26 at the time.

His handwriting’s almost suspiciously neat, the man comes across as precise and gentle. The letters are long; several sheets layered one upon another and folded.

At the bottom of the box, there’s a single letter written by my mom on a typewriter. I reckon it may be a copy of an actual letter that she decided to keep for herself.

There’s a sentence that my eyes absorb instantly: (…) I’ve been thinking about you and our relationship and I came to the decision (…), and from this single line, I can feel my mother, the parts of her I know: strict, worried, precautious.

But I know there’s her other self that enabled my own life: courageous, stubborn, dreamy, determined, idealistic. Who’s my mother, after all? To get to know one’s mother: to walk her landscape.

Although I’m infinitely curious about the content of those letters – longing to get to know my mother as a young woman in love, to read the lines that she had read from a man who must have loved her so much, a man who was not my father, although I really do – the respect for her privacy is what stops me in the tracks. Or maybe it’s something else. Am I perhaps afraid? But what would I be afraid of?

I close the box and carefully tie the ribbon around it, yet I can’t quite imitate the original intricacy of the knots. I’m thinking about when was the last time she had opened it…and for how long she kept reading the letters.

I tuck the object in the very back of the shelf.

In the dark of the closet, I notice another red box, a little narrow one – still in the mood for a mystery, I slowly open it and realize it’s the one where my mother keeps the humble collection of family gold. Among the jewelry, I recognize my grandmother’s wedding ring, and I notice that its rim is thinned on one side by the countless wearings. Next to it lies the pair of golden earrings my mother used to wear when I was a child, before she abandoned the woman in her, and I’m reminded of how I always liked those. Their shape reminds me of two large seeds, elegant and peculiar. I drop them into my palm, examining them, so precious.

I walk into the bathroom and hold my breath while I, almost religiously, put them on. I gaze at my face in the mirror which suddenly looks unfamiliar; these earrings lend to my face an air of something I cannot define. I keep turning my head left and right, trying to gauge if I like them on me or not. Staring at the woman in the mirror I realize I am at the age when my mother wore those earrings, when I used to reach for them, little shiny things, with my little hand, and then I hurriedly take them off and drop them back into the box, as if worried that with this act I might have provoked some opaque, ambiguous magic, that must for sure be inscribed in this kind of sacred objects.